Now that you've spent time drooling over the latest and greatest audio gear, and invested some of your hard-earned cash in decent equipment, you need to figure out how to hook it all up and produce professional sounding podcasts. The great thing about working with audio is that for a minimal investment, you should be able to produce your podcast to a very high standard. The powerful technological leaps we've seen in the world of computers have also brought great advances (and price drops) in the world of home recording. What once required thousands of dollars worth of equipment now costs hundreds, or less.

We will start off showing you how to connect your equipment to get the best sound, and then talks about some general recording techniques. Audio production may seem daunting at first, but by setting up some simple procedures and sticking to them, you'll find it to be pretty simple, and more important, lots of fun.

After that, we cover editing, where much of the power of audio production actually lies. Good editing can transform your podcast from mundane to professional. The techniques described are all standard operating procedure in radio, television, and recoding studios around the world. Though we can't hope to turn you into an audio engineer in a few short pages, we can at least point you in the right direction. Let's start by setting up your equipment — the right way.

Setting Up Your EquipmentDifferent kinds of equipment you need to produce your podcast to a high standard. Ideally, you took the plunge and bought some equipment to fit your budget and the scale of your production. Now it's time to unpack everything and connect everything together. This is actually a critical step in podcast production. If you set up your equipment incorrectly, you'll leave yourself vulnerable to noise, interference, and distortion, which will compromise the sound quality of the final production. If set up correctly, your hardware will have you on the road to creating broadcast-quality programming. To understand why this step is important, you have to understand the concept of gain.

Setting your levels

Gain, also known as level, is the measure of the power of your audio signal. When using analog audio equipment, such as microphones and mixing desks, the signal is a continuously varying voltage. The higher the voltage is, the higher the gain and the louder the audio. All audio equipment is designed to work within a certain known range of voltages. To obtain the best possible quality out of your audio equipment, without adding any noise or distortion, you want to work within the optimal range for that piece of equipment, known as its dynamic range.

Dynamic rangeThe dynamic range of a piece of audio equipment is the difference between the loudest sound it can handle without distortion and the internal noise floor of the equipment. For example, when you turn a portable radio up too loud, you'll hear the sound crackle and buzz; that's distortion. You've just exceeded the dynamic range of the radio. The noise floor lies at the other extreme of the spectrum.

All audio equipment produces some amount of noise; there's no such thing as a perfectly quiet piece of equipment. That's because they're imperfect by definition. Every piece of audio equipment has all kinds of electronic components, each one adding a minute amount of noise, which taken in total is the noise floor. You can hear this noise — just turn your stereo up really loud while you're not playing anything. You'll hear a hissing and possibly a buzzing noise. This is the system noise that is being amplified. If you were actually playing a CD, you wouldn't hear this noise, because the music would be much louder than the noise.

More expensive equipment uses better components, which produce less noise. Consequently better equipment has a greater dynamic range. Cheaper equipment, well, you get the idea. This is the argument for investing in decent audio production equipment. If you produce audio with no audible noise, your podcast sounds much better. Noise is a dead giveaway that an amateur is behind the controls. Another giveaway is distortion. After your signal distorts, you can't remove the distortion. It can't be edited out of the signal, and it compromises the quality of your podcast.

Dynamic range is measured in decibels (dB). The human ear is capable of perceiving up to 120-130dB of dynamic range, before the pain threshold kicks in. We can hear a faucet dripping down the hall in the middle of the night, and endure hours in front of our favorite rock band. Our ears are extremely sensitive, which is not necessarily the case with the equipment and/or transmission methods used to produce audio.

Different audio transmission methods have different dynamic ranges. For example, compact discs have about 96dB of potential dynamic range, whereas FM radio has only about 70dB of dynamic range and AM radio has only about 48dB of dynamic range. This is because of the noise inherent in each system. If you think about it for a second, the quality differences between these systems is obvious. The larger the dynamic range is, the higher the quality of the audio signal and the less apparent any noise is.

Using meters to monitor levelsTo control your levels, you need to keep an eye on your meters. Virtually every piece of audio equipment comes with some type of meter to indicate the level of the signal. Meters fall into three main categories: VU meters, LED Peak meters, and software VU/Peak meters, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A software VU/Peak meter Courtesy Sony Sound Forge

Figure 1: A software VU/Peak meter Courtesy Sony Sound Forge The first is VU or Volume Unit meters, which are common on older equipment (and new equipment going for that hip retro look). The needle indicates the overall power of the signal, represented as an average. They're very good for comparing the volume or power of a signal, but not good at registering quick peaks. VU meters usually have two scales, one that runs from 0 percent to 100 percent, and another that has zero where the 100 percent mark is, with negative numbers below 100 percent and positive numbers above 100 percent.

The next type of meter is the LED (Light Emitting Diode) Peak meter. LED meters are very fast, so they are generally used to indicate the peak values of the audio signal. LED meters generally have a single scale, measured in dB, running from approximately -40dB, up through zero, and on to +10 or +20dB.

Note Decibels are a relative measure of power. The decibels used to measure the +20dB measurement on a meter aren't the same as the 120dB pain threshold. One is a measure of sound pressure, while the other is a measure of voltage. It can get kind of confusing

Finally, we have the software meter. Software meters can operate as VU or LED meters, and sometimes as both concurrently. In the image on the right of Figure 1, the meter indicates both VU level (the bulk of the display) and peak level (indicated by the thin line hovering above the VU level). The critical difference between analog meters and software meters is that analog meters have headroom, which means that the signal is allowed to go above zero, and digital meters have no headroom: Go above 0dB, and you'll hear awful square-wave distortion, which is very unpleasant. Digital meters usually include some sort of clip or peak light that indicates when you have peaks above zero. These must be avoided at all costs.

The point of all this is that you need to be careful when setting up your equipment Set your input level too low, and you're liable to hear some of the internal noise of your equipment. Set your level too high, and you'll get distortion. What you want to do is set a level that is high enough so that you don't hear equipment noise and conservative enough that you don't ever get distortion. It's a fairly broad range, so spend the time to learn how to set levels correctly. The result will be a much higher quality podcast.

Setting levelsWhen setting a level with a VU meter, be careful because VU meters don't register peaks. Those peaks may be loud enough to exceed the equipment's dynamic range and therefore cause distortion. It's best to set your levels between -10dB and -6dB on a VU meter. This leaves quite a bit of headroom for transient peaks, and any unexpected jumps in level. When you're setting levels with a peak meter, you can be a bit more aggressive, because you can see pretty much exactly where your peaks are. You should set your level so that the indicated level is in the -6dB to -3dB range. These settings should get you a good, clean, loud signal, with very little perceivable noise. If your levels occasionally peak above zero, don't worry; most audio equipment has sufficient headroom to handle momentary peaks without distortion.

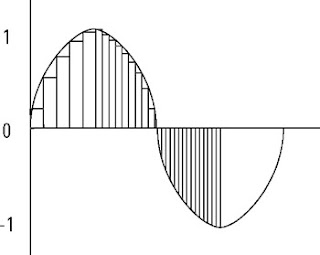

Setting levels in the digital domain is a whole different matter. Any signal above 0dB causes distortion, because 0dB is considered an absolute maximum. As long as the signal remains above 0dB, you keep getting the same maximum value. The result is a sound wave with the top squared off, which sounds horrible. This is known as square-wave distortion.

You must be conservative when setting levels on digital equipment. Digital meters are almost always peak meters for precisely this reason. When setting your digital levels, you should target -10dB to -6dB. This should leave you plenty of headroom. It's better to be a little conservative and maximize your level later on using signal processing rather than set it too high and end up with distortion.