Rods can operate at widely varying light levels, but cones require more light, which is why we can see at twilight, but things don't look as colorful. So if we want to record the highest possible video quality, with all the color information, we need enough light so that our cones will respond and relay the information to our brains. This is a fairly long-winded way of saying "use lights." The more light that's present, the more color information and detail we'll be able to perceive.

The amount of light in a video signal is referred to als luminance. The amount of color in a video signal is referred to as chrominance. So when we're working with light, whether we're recording it or manipulating it, we are working with luminance and chrominance. The tricky thing is that luminance and chrominance are intricately intertwined. If you add more luminance, the chrominance is affected. Think about adjusting your television set or your computer monitor. When you turn up the brightness control, colors appear brighter, which may or may not be what you want.

Color

Color is very subjective. We can never truly know how someone else perceives color, but our eyes are constantly adjusting to colors depending on the amount of light available. For example, if someone is wearing a red shirt, his shirt looks red whether he's outdoors in the sunlight or indoors under fluorescent lights. The quality of light that is being reflected off his shirt is completely different in these two situations, but our eyes adjust, and we see the shirt as red.

In a following section, you learn that cameras attempt to do the same thing, but they often need a little help. Making sure your camera is recording color information correctly is known as white balancing your camera. You must white balance your camera, preferably before every shoot, and every time your lighting situation changes.

Using lights

Many cameras are sold on their ability to shoot in low-level lighting situations. Although this may be okay for a home movie, if you're trying to create a broadcast-quality podcast, you need some lights. Shooting with the proper amount of light adds color and detail to your presentation, making it look higher quality. Also, when you encode your video into a podcasting format, you'll find that the higher quality your original is, the higher quality the resultant podcast is.

Discussing the finer points of lighting video is far beyond the scope. Many good books are available on the subject, as well as plenty of lighting professionals who are looking for work. But in the interest of giving you a firm understanding of lighting basics, we discuss the basis for virtually all lighting schemes, which is known as three-point lighting.

Three-point lighting

Three-point lighting is a simple technique that uses three lights to achieve a satisfactory lighting effect. These lights are known as the key, fill, and back lights. Each fulfills a specific purpose:

- The key light is the main light source for the scene.

- The fill light is the secondary light source and fills in the harsh shadows created by the key light.

- The back light is used to separate the subject from the background, by highlighting the shoulder and hair line.

For a simple illustration of three-point lighting, take a look at the three photos in Figure 1.

In Figure 1a, we see the subject as lit by a single light. We can see the subject, but the left side of the subject is almost completely in shadow. To remedy this, we add the fill light, to fill in the shadows created by the key light (as shown in Figure 1b). The fill light remedies the problem with the shadows we had with a single light source, but the image is very flat. The subject blends into the background, creating a two-dimensional, lifeless image. To remedy this, we add the back light (as shown in Figure 1c). With the back light added, we now see the subject's hair line, as well as highlights on both shoulders. This helps separate the subject from the background and gives us a much more three-dimensional image.

Placement of the three lights is fairly straight forward, as illustrated in Figure 2. The key and fill lights are placed in front of the subject, on either side of the camera. They are usually slightly above the subject, pointing down slightly. The back light is obviously behind the subject, to one side, and usually placed fairly high, aiming downward.

One thing to bear in mind when setting up your lights is the quality of the light. Light sources can be hard or soft. Hard sources cast very strong shadows. For example, if you shine a flashlight against a wall in a dark room, the resultant beam has a defined round shape, with a very distinct edge. Anything in the path of this light creates a very distinct shadow. Soft light sources are more diffuse and cast softer shadows. For example, a lamp in your living room with a lampshade casts a very soft, diffuse light. The shadows cast by this kind of light are very soft and undefined.

In general, you want a relatively hard light source for your key light, a soft source for your fill light, and a very hard source for your back light. The shadows cast by the key light let people know what direction the light is coming from (which is important to our sense of depth) and are softened somewhat by the fill light. We don't want shadows from the fill light to be noticeable. We want the back light to be hard so we can pinpoint it where we need it. We don't want back light spilling all over the place.

Professional lights usually include a lever or dial that allows you to choose between hard or soft light. If you want to soften a hard light source, you can either put a diffusing material in front of it or bounce the light off something reflective. You can purchase attachments for your lights that change a light source from hard to soft.

Another thing to consider is how bright each light should be. The key light should be the brightest, because it's the main light source. The fill light should be lower wattage, so that it doesn't overpower the key light. The backlight should also be lower wattage than the key light. If your lights are all the same wattage, you can compensate by moving lights closer to or further away from your subject. A little adjustment can go a long way. For those of you who remember your physics classes, light falls off using the inverse square law, so double the distance equals one quarter the light.

Of course, in a situation where you have more than one subject, your lighting can be much more complex. You'll very likely need more than three lights. However, three-point lighting is still the basis of most lighting situations. You're always going to need a main (key) light source, fill lights to fill in shadows, and back lights to separate your subjects from the background.

Using reflectors (bounce boards)

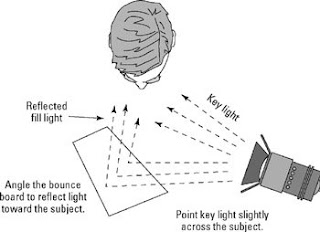

One way to economize if you're stuck without enough lights is to reflect light from your key off what are commonly called bounce boards. Bounce boards can be as simple as a piece of light-colored cardboard to purpose-made reflectors that fold up into small, portable packages. Videographers usually travel with a couple of these in their arsenal because they're light and useful in lots of different situations.

This works quite simply. Instead of focusing the key light directly on the subject, you direct it slightly across the subject. Then you can reflect some of this light from a bounce board back toward the subject, as shown in Figure 3. Because the light is being reflected, it's automatically a diffuse source. It's also much lower intensity after being reflected, so it won't compete with the key light.

This setup is commonly used in video news reel (VNR) situations. Interview teams often consist of a single reporter and a cameraperson, so traveling with a full three-point lighting kit is impractical. Instead, the cameraperson brings a single light on a stand and a bounce board, which may even be held by the interviewer while he's asking questions! It's cheap and portable, and quite possibly ideal for video podcasts.

Shooting outdoors

If you're shooting outdoors, the main problem is that you have no control over your key light, which by definition is the sun. You can't control how bright it will be, or how hard or soft. On a sunny day, it will be a very hard source. On an overcast day, sunlight is very diffuse. It's ironic, because everyone wants to take photographs on sunny days, but sunny days can be the most challenging situations in which to work.

Another problem with working outdoors is power. It's not like you can bring a lighting kit and plug it in wherever you want. You may have the option of battery-powered lights or a generator, but this starts to go beyond the scope of most video podcasts. What you'll most likely want to do is make judicious use of bounce boards to try to even out the lighting available to you. It also can be quite a bit easier to work out of the direct sunlight, and shoot your video in a shady area. You still get the warm quality of the sunlight, but without the harsh shadows that can be hard to overcome.

No comments:

Post a Comment